How Currency Intervention and Manipulation Works

Looking at Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, and China to understand currency manipulation

The topic of currency manipulation pops up annually in the US around the timing of the US Treasury’s annual report on the topic. It’s also typically a hot topic around election seasons. There’s often talk of China intervening in the market to keep their currency relatively cheap. But what does that really mean? How does that process work? The goal here is to shed some light on that topic in layman’s terms.

What are the different types of flows?

First an overriding assumption to get going. Let’s assume that the amount of all currencies in circulation is fixed.

Let’s start out simple. Let’s say Country X sells goods to the rest of the world and receives Currency Y for those goods. It wants to convert that to Currency X because that’s what it lives on and how it pays people. So there is demand from people or businesses wanting to buy Currency X and sell Currency Y. That pushes up the exchange rate of Currency X vs. Currency Y.

At the same time, Country X is buying goods and importing from the rest of the world. In other words, there are those needing to sell Currency X to buy Currency Y, which puts downward pressure on the value of the currency.

Taken together, if Country X exports more than it imports, then there is more demand for Currency X vs. other currencies and it appreciates in value vs those other currencies.

That’s one source of foreign exchange flows: trade. It is rolled up into another category called the Current Account ("current" in this context means during the "current period") which is basically the trade balance.

However there’s another big source of foreign exchange flows (there’s actually bunch more, but for simplicity we’re going to ignore them and they tend in general to be less significant). Let’s assume there is a company that wants to invest in Country X and either build a factory, open a store, or make some other sort of investment. It will need to acquire Currency X in order to do this and sell its own currency. That puts appreciating pressure on Currency X vs. other currencies. These are investment flows.

As with trade, there are both inflows into a country, and outflows from a country to another. Depending on how those net out, there is either an appreciating or depreciating pressure on the currency.

There’s one more related type of flow. Let’s assume you want to buy a stock or bond listed in Country X. Perhaps you think the stock is cheap or that you like the interest rates available in Country X. To do this, you need to sell your own currency to buy Currency X. That puts appreciating pressure on Currency X vs. other currency. These are portfolio flows.

So in big picture terms, we have trade flows, investment flows, and portfolio flows impacting the foreign exchange rate.

OK, so then what happens?

In theory, as a currency becomes more valuable against others, it makes the price of its exports more expensive. There is then less demand for those exports, the appreciating pressure subsides, and the value of the currency might stabilize at a new equilibrium.

Similarly, if interest rates decline in one country while they stay the same in others, there might be less demand for that currency since the financial returns are no longer as attractive vs. alternatives. Portfolio flows might be outward seeking better alternatives elsewhere.

How does intervention, or manipulation, come into play?

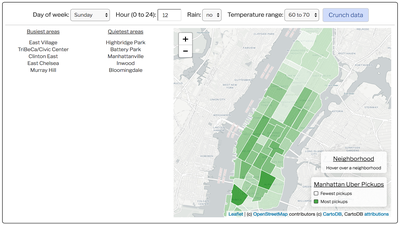

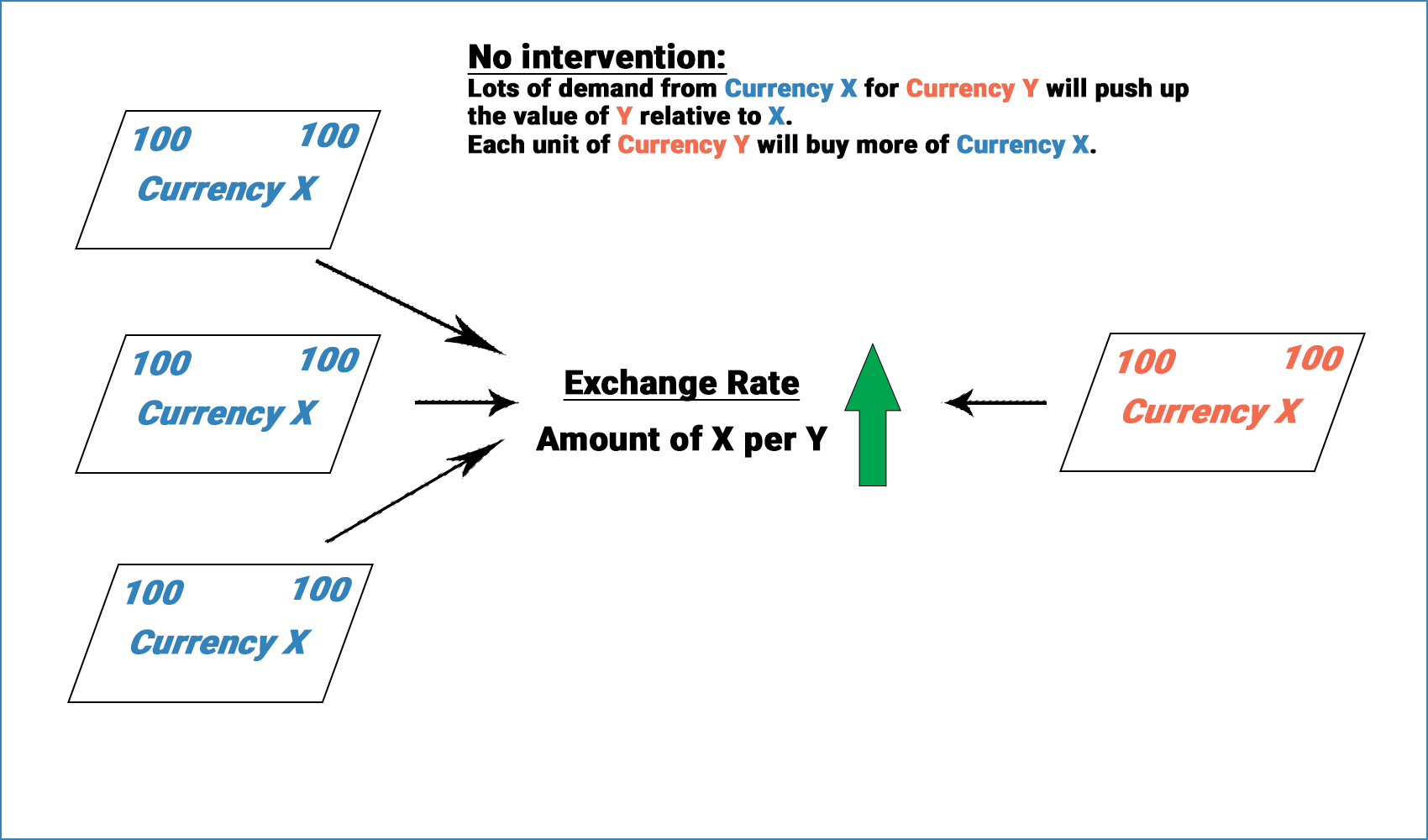

So everything we’ve talked about so far assumes that there is no intervention. If a country exports a lot of goods, the price of its currency becomes more expensive vs. others as companies sell other currencies to buy Currency X to pay for the goods and services. The value of Currency X will go up, making these goods and services less attractive at the new exchange rate, reaching a new equilibrium as people that use to buy from Country X might go look for cheaper alternatives elsewhere. The graphic below tries to illustrate this point.

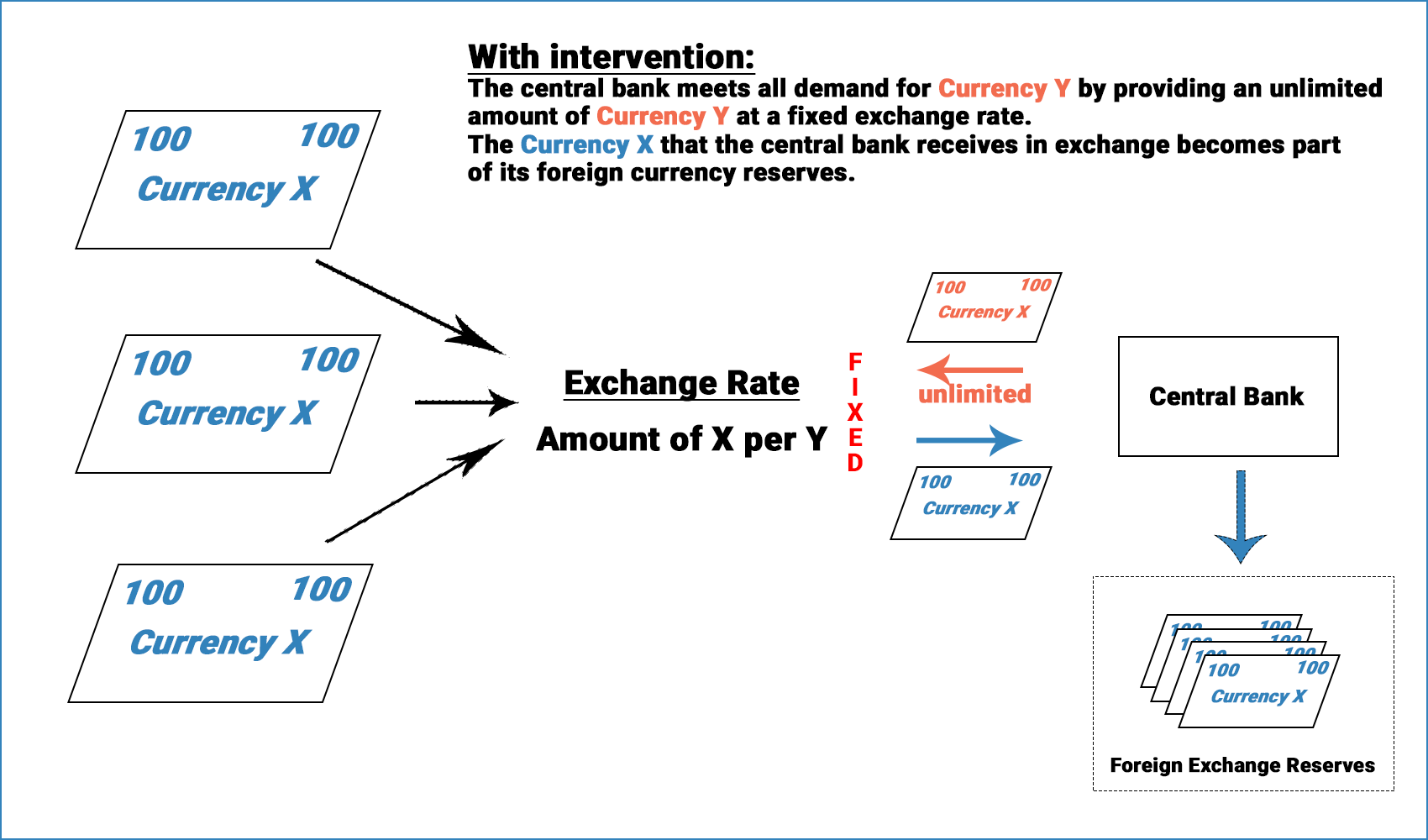

So now lets introduce intervention. If a country’s central bank intervenes in the process, they typically step in the middle of the transaction and offer up an unlimited supply of Currency X at a particular exchange rate. So even if people want to buy more and more of Currency X, the central bank will keep supplying new currency to them at the chosen exchange rate. This prevents their currency from appreciating since the supply is no longer fixed.

When this happens, the central bank accumulates what are called “foreign exchange reserves”. It’s the money it’s bought in the market to keep control of the exchange rate at a determined level.

This works in the other direction too, but with an important caveat. A central bank can also prevent its currency from depreciating, but only so longs as it has foreign exchange reserves to satisfy the demand for other currencies. If it no longer has those foreign exchange reserves, it can’t intervene, and its currency might collapse in value vs. other currencies.

There are additional implications for a country intervening in the currency markets, but those are beyond the basics outlined here.

An example: Saudi Arabia - Trade flows

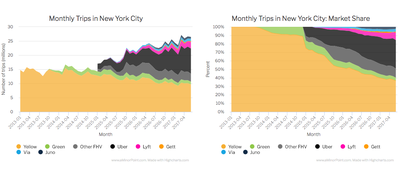

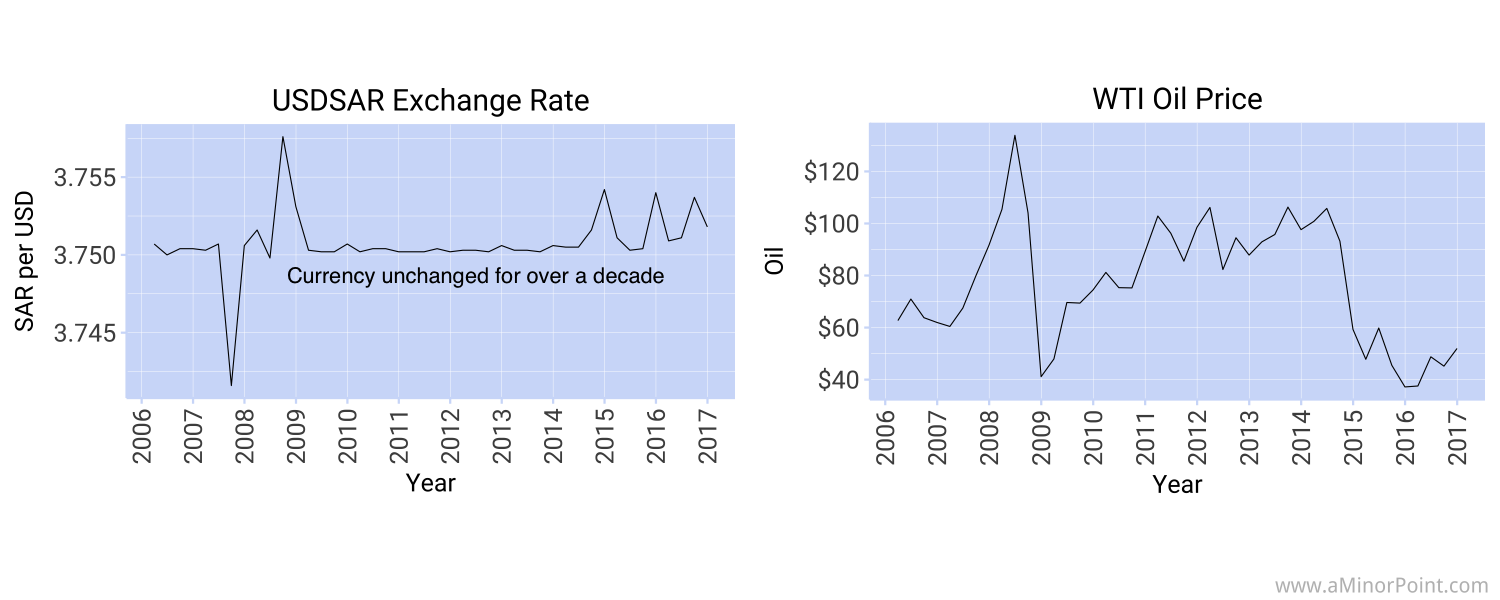

Saudi Arabia exports oil. A lot of it. The value of their oil exports dwarfs their import needs so that the country runs a very large trade surplus. But rather than this surplus leading to upward pressure on the Saudi Riyal (SAR), the government has decided to keep the value of the SAR fixed vs. the US Dollar (USD). It’s been this way for a long time. USD 1 will buy you SAR 3.75. This has held despite swings in the oil price. The charts below illustrate this point.

Because the central bank (Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority, or SAMA) has fixed the exchange rate at 3.75, they are intervening in the market and manipulating the value of their currency. They are supplying an unlimited amount of SAR at that exchange rate and accumulating a large amount of USD as foreign exchange reserves as a result.

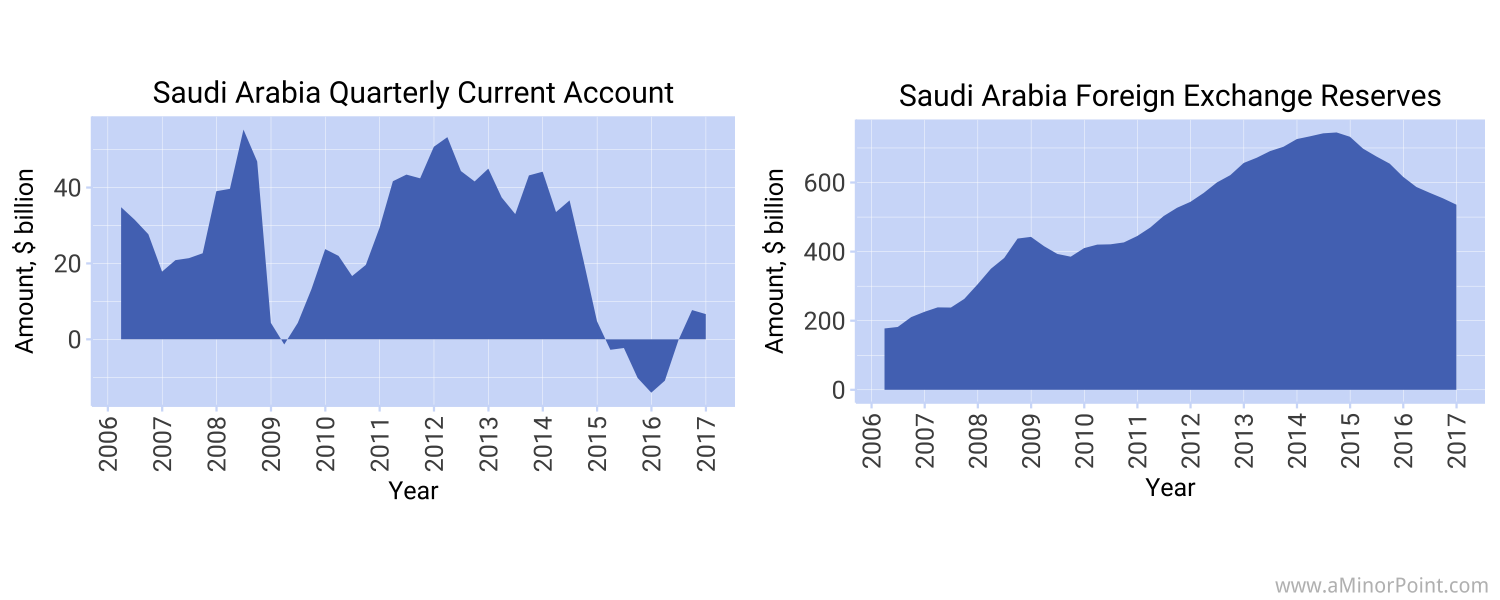

At its peak, SAMA had accumulated around $750bln in foreign exchange reserves in the middle of 2014. This was after years of high oil prices during which the country ran a very large trade surplus. But this changed in 2014 when oil went from $100 to $50 in the span of six months. The trade balance went from a surplus of $40bln per quarter to a trade deficit. This meant that the country was no longer accumulating reserves. Instead, it started spending reserves to maintain the value of the currency at 3.75. In addition, the government began using the reserves to meet its spending needs since it had budgeted for a much higher oil price. So starting in the summer of 2014, SAMA’s foreign exchange reserves began declining. As of April 2017, the balance was down to $500bln. The charts below illustrate this point.

Should the country run out of reserves, the value of their currency would begin declining against the USD. This would make imports more expensive and pose other challenges. But there are also other steps the country can take (and is taking) to stem the decline in reserves.

An example: Switzerland - Portfolio flows

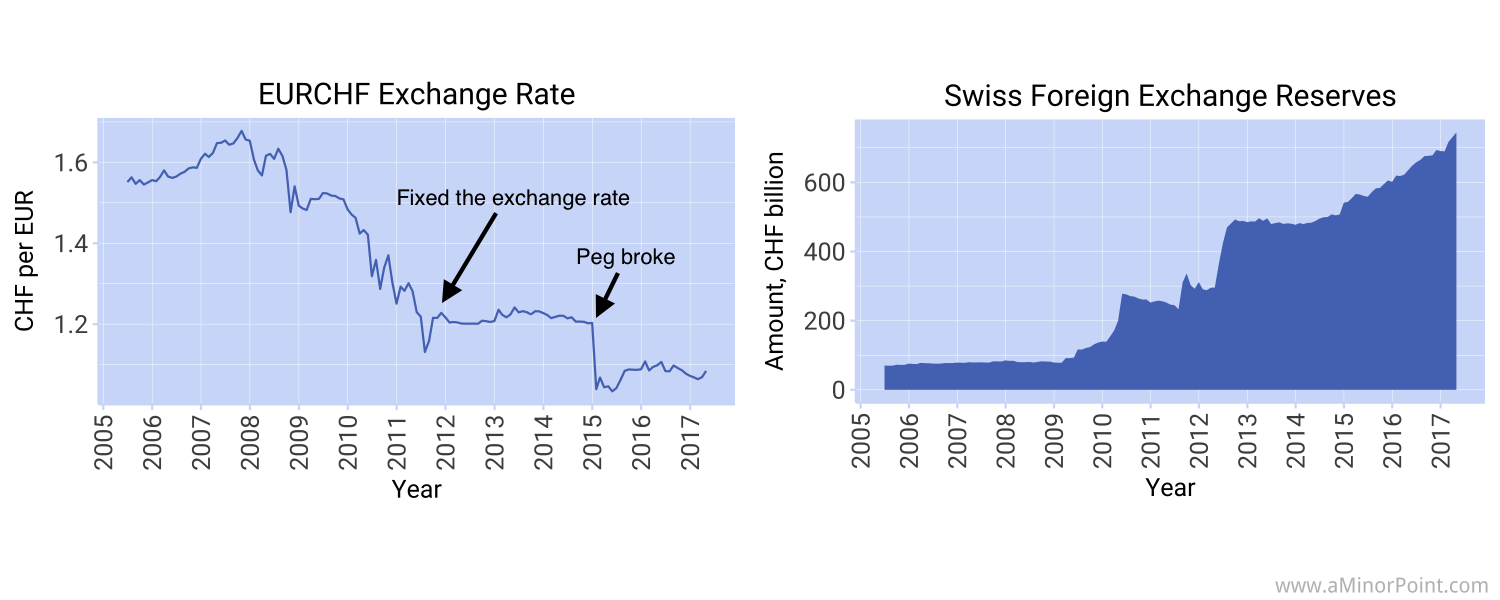

Switzerland sits in the heart of Europe as is viewed as a safe haven. This became amplified during the Eurozone crisis that developed from 2009 onwards when there was real doubt about the sustainability of the Eurozone and whether or not it would break up. As the worry intensified, people became concerned about the value of their Euros (savings, investments, etc…) and began converting them to Swiss Francs (CHF) to try and maintain their value and reduce the risk. This began to put significant appreciating pressure on the value of the CHF vs. the EUR. Unlike the Saudi Arabia case, this was due to portfolio flows, not trade flows. The flows became so large that in the fall of 2011 the Swiss National Bank (SNB) released the following statement:

Swiss National Bank sets minimum exchange rate at CHF 1.20 per euro

The current massive overvaluation of the Swiss franc poses an acute threat to the Swiss economy and carries the risk of a deflationary development.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) is therefore aiming for a substantial and sustained weakening of the Swiss franc. With immediate effect, it will no longer tolerate a EUR/CHF exchange rate below the minimum rate of CHF 1.20. The SNB will enforce this minimum rate with the utmost determination and is prepared to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities.

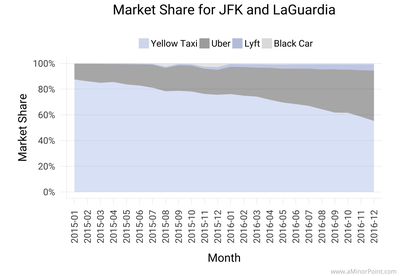

As a result, the SNB would sell as much CHF and buy as much EUR as the market desired at the 1.20 exchange rate. This led the SNB to accumulate significant amount of foreign currency reserves. The charts below show the sharp decline in the EURCHF exchange rate (appreciating CHF) and the corresponding change in reserves.

Ultimately the SNB decided to abandon the peg at the start of 2015 for various reasons. This caused the CHF to appreciate in an instant against the EUR.

An example: China - Trade and portfolio flows

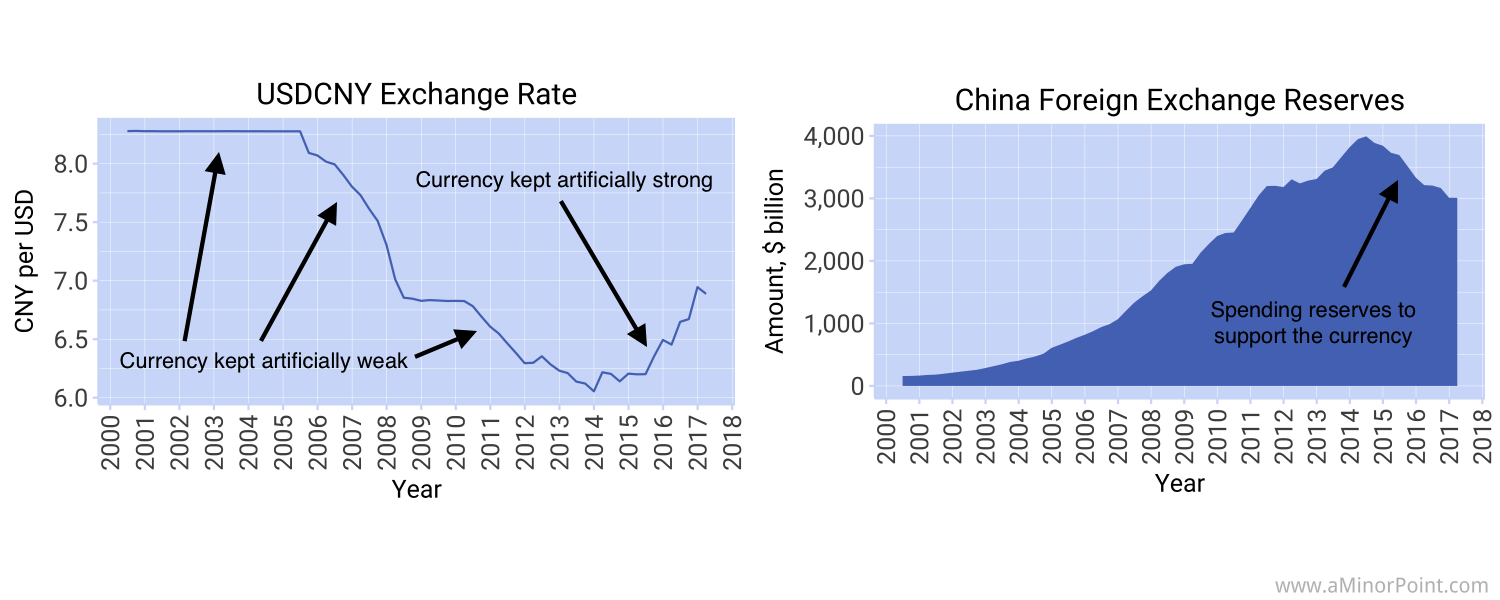

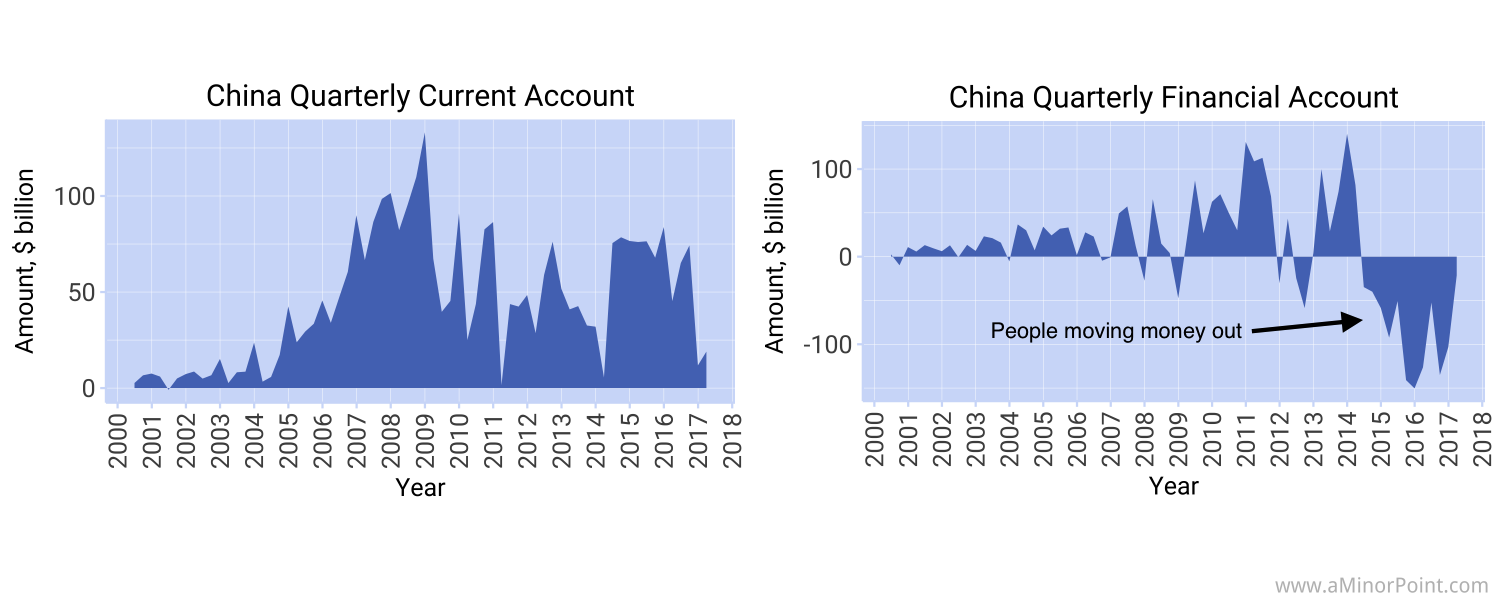

China is the country most frequently discussed in the context of currency intervention and manipulation. In the early 2000s the exchange rate against the USD was fixed. As China became a significant exporter, it began to accumulate foreign exchange reserves at that fixed exchange rate. In 2005, the country changed policy to allow for the CNY to appreciate against the USD, but at a controlled rate. Despite the gradual appreciation, the trade balance remained in surplus and the country accumulated foreign exchange reserves at an accelerating rate. However things changed in 2015 when the CNY exchange rate was moved lower against the USD. This was accompanied by a switch from foreign exchange reserve accumulation to a drain of foreign exchange reserves.

The trade surplus is not what changed. It continued to run between $25bln to $75bln per quarter. So on its own and with the country’s currency policy, the country should have been accumulating foreign exchange reserves. But this trade surplus was being more than offset by portfolio flows. Specifically, it reflected Chinese trying to convert their CNY into other currencies, mainly the USD. In the latter part of 2015 and into 2016 Chinese savers and investors were moving upwards of $150bln per quarter into other currencies.

The reasons for this move varied and include the increasingly attractive US interest rates as markets anticipated the Federal Reserve increasing rates, as well as a general concern locally that the CNY was going to depreciate. This period also saw an increase in Chinese companies buying foreign companies as a way to move money out of the country. Regardless of the precise reason, the Chinese authorities decided to resist the depreciating pressure on the CNY by selling some of their foreign exchange reserves and buying the CNY that locals were trying to sell. To date the country has spent almost $1 trillion trying to prevent the currency from depreciating in response to outflows from within China.

This represents a marked shift in China’s currency policy. Since the summer of 2015 the country has been intervening and manipulating its currency. But unlike in the past when it was done to keep the currency relatively cheap to support a growing export sector, it is now being done to try and prevent the currency from collapsing relative to other currencies. It has spent upwards of $1 trillion doing so to have the currency depreciate at a more moderate and controlled pace.

So be cautious around overly simplistic views that China is manipulating its currency to help its exporting companies. That used to be the case a decade ago. It’s more complicated now and China has been intervening to prevent its currency from depreciating, something that seems to get lost a lot in discussions that rely on out-of-date views and data.